As the farm-to-table movement takes hold globally, a technology-enabled revolution is brewing that could fundamentally change the way restaurants source fresh produce.

Indoor farms are popping up in urban areas across the country promising a wealth of short-growing-cycle produce in a way that is truly local.

Out of tiny shipping containers, on rooftops or in converted steel mills, these climate-controlled farms are producing everything from micro greens and leafy lettuces to mushrooms and tomatoes.

The produce can be delivered to restaurants just hours after harvest and year round. There are no variables for weather or global warming; no need for pesticides or herbicides. In fact, in some cases, there’s no soil involved.

These farms use hydroponic, aeroponic or aquaponic technology. Some are in greenhouses using natural light and some use shelf-like stacked planes or vertical growing walls with LED lighting. One shipping container, for example, can produce as much as two acres of farmland. Unlike outdoor farms, however, the indoor versions can repeat the growing cycle over and over, 52 weeks per year.

These urban farms can produce food with 95 percent less water than conventional farms, no run off or soil-stripping issues and food-safety can be strictly controlled from seed to restaurant delivery in a way that isn’t possible with acres of land exposed to wildlife, pollution and pests.

Early adopter Erik Oberholtzer, co-founder and CEO of the Los Angeles-based fast-casual chain Tender Greens, envisions a not-too-distant future where restaurants and distributors will be able to tap a network of farmers that are transforming their communities and creating jobs by reactivating long-dormant mills and warehouses as urban farms or collectives.

“This is a disruptor. It is definitely changing the way we relate to food and the way we relate to farming,” he said. “There are those who worship the soil and are very against aquaponics and hydroponics and other methods of urban farming. But I’m a believer that there’s room for both traditional farming and urban farming and we intend to support both as we grow.”

The tipping point: Price

The technology is relatively new, but startups are popping up across the country and poised for growth, many supported by investments by national retailers like Costco, Whole Foods Markets and Safeway.

Altitude chef Justin Christy beside a Bright

Agrotech ZipGrow wall (Photo by Nikkita Miller)

Gotham Greens, for example, boasts more than 170,000 square feet of urban greenhouses on the rooftops of four facilities in New York and Chicago — including the roof of a Whole Foods Market — producing up to 10 million heads of leafy greens and herbs every year.

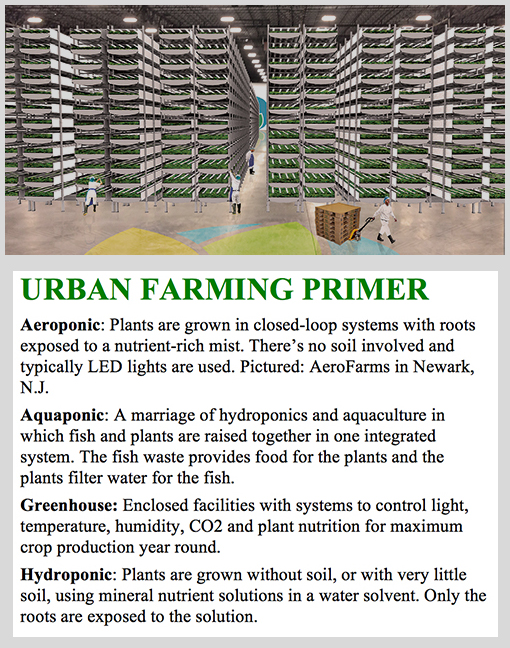

In New Jersey, AeroFarms recently opened a 70,000-square-foot aeroponic vertical farm in a converted steel mill in Newark. The company plans to build 25 urban farms over the next five years.

Infinite Harvest, based in Lakewood, Colo., operates a 5,400-square-foot hydroponic farm producing lettuces, arugula, kale, basil and other herbs for restaurants in the Denver area. Using stacked vertical planes, the facility is the equivalent of about an acre of farmland, if laid out flat, but produces 24-acres-worth of food in a year.

As such companies grow, the price of urban-farmed produce has come more in line with that of boutique and organic farms, said Oberholtzer.

Tender Greens buys from Go Greens Agriculture, which has a six-acre indoor hydroponic farm in Encinitas, Calif., and a second 14-acre unit under construction in Northern California.

Positioned more for the mass market, Go Greens is targeting growth of its farms close to distribution centers. But about 40 percent of business from the Southern California location is direct to restaurants, with trucks delivering within a two-hour driving radius each day.

Go Greens is one of only a handful of hydroponic farms certified organic by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. While organic certification for such farms is currently allowed, a task force is considering separate rules specifically for urban farms using soil-free technology.

Tender Greens also buys from Local Roots, a collection of shipping container “TerraFarms” in downtown Los Angeles. Local Roots is pitching its modular “plug and play” farms to universities, hospitals, foodservice distributors and other hospitality settings.

For the 24-unit Tender Greens, urban farming will be key as the brand makes its move to the East Coast for the first time later this year. Oberholtzer said he’s looking at Gotham Greens to supply future restaurants in the New York area.

“Our vision was always to have a system that could scale with the expansion of Tender Greens and to grow those ingredients we knew we didn’t want to ship,” he said. “Lettuces and herbs and the most delicate of plants we wanted to grow as close to the restaurant as possible under the best conditions as possible.”

“Our vision was always to have a system that could scale with the expansion of Tender Greens and to grow those ingredients we knew we didn’t want to ship,” he said. “Lettuces and herbs and the most delicate of plants we wanted to grow as close to the restaurant as possible under the best conditions as possible.”

As the growers grow

Marc Scheuer, senior vice president of culinary for New York-based institutional foodservice provider Restaurant Associates, sees urban farms as a supplement to the conventional farms the company buys from.

Restaurant Associates uses greens from AeroFarms at five or six outlets throughout the city, said Scheuer, and soon will use more as AeroFarms expands. Scheuer said he hopes to eventually source greens for all 80 of RA’s outlets across New York City.

“The fact that we can have greens year round is huge,” said Scheuer. “Our clientele loves the story behind it. Anything to shrink the carbon footprint, and to bring jobs to an area with low unemployment. The message is great.”

AeroFarms’ greens are slightly more delicate than conventionally raised products, but just as flavorful, if not more so, Scheuer said.

“They can stress the plant to create more spiciness. I did a side-by-side comparison and it was amazing how much spicier the [AeroFarms] arugula was,” he said.

Vertically farmed produce is also cleaner than field-raised greens, Scheuer noted. “No one wants to find a bug in their salad.”

And RA has worked with the farm to buy a second cut of kale, for example, which includes more if the stem-side of the leaf that might otherwise be discarded.

“We mix it on the salad bar and call it kale sprouts. People are all over it,” said Scheuer.

Farming in a dessert community

In Las Vegas, Urban Seed in July broke ground on a 6,400-square-foot aeroponic greenhouse that aims to bring locally grown, non-genetically-modified fruits and vegetables to the desert community. Unlike most indoor urban farms that rely on LED lighting, Urban Seed uses natural sunlight. The plan is to produce everything from beets and basil, to “cucamelons” and strawberries.

Photo courtesy of Infinite Harvest

Mary Sue Milliken, co-owner of the Los Angeles-based Border Grill restaurants, serves on Urban Seed’s culinary board.

Mary Sue Milliken, co-owner of the Los Angeles-based Border Grill restaurants, serves on Urban Seed’s culinary board.

For years, Border Grill Las Vegas has relied on produce trucked from Southern California and elsewhere, but those travels hurt the freshness and flavor, she said.

Urban Seed was scheduled to start supplying Border Grill and other restaurants across Las Vegas by March. Milliken said she had high hopes for items like cilantro, which the Mexican-inspired restaurant uses a lot of.

“That’s a very delicate herb, and if it can be grown two or three blocks away year round and it tastes great, that’s a win,” she said.

But at press time, she hasn’t yet tasted the product. “I told them all along that if I detect a difference in flavor, I’m going to go with the best tasting product, no matter what. If the tomato doesn’t really taste like a delicious tomato, then it’s not going to work.”

For these young farms, there will likely be a learning curve, she noted.

As a chef, Milliken doesn’t love the idea of erasing seasons with a product that can be grown year round.

“In the future, people might not really have a sense of when pear season or strawberry season is. To me, that’s kind of a loss,” she said.

“But I can’t look science in the eye with any kind of conscience and say it’s silly to eat something out of season or to take away the soil when it comes to finding a way to feed 8 or 9 billion people on the planet. And this technology could make that possible,” she added.

Farming in the city

Tobias Peggs, co-founder and CEO of the New York-based urban farming startup Square Roots, sees the urban farming movement as a solution to that larger problem.

By 2050, the planet will host some 9 billion people, and 70 percent of them will live in cities, he said.

“If these people want real, local food, then we’ve got to figure out how to grow food in the cities, at scale, as quickly as possible,” he said.

Co-founded by restaurateur and tech entrepreneur Kimbal Musk, Square Roots plans to build 20 “urban campuses” of shipping container farms by 2020 in various cities with the goal of empowering a next generation of farmer entrepreneurs that will lead what Peggs calls the “real food revolution.” The individual farmers sell to restaurants, distributors or direct to consumers.

The first campus in Brooklyn opened last fall with 10 “founding entrepreneurs.”

Photos courtesy of Square Roots

Photos courtesy of Square Roots

The restaurant Egg Shop in New York (left), for example, supports those farmers by hosting a quarterly “Know Your Local” farmer’s market at the restaurant where customers pack in on a Monday night to have cocktails made with Square Roots herbs and buy freshly harvested greens.

“This is less about a food transaction or a food vendor relationship,” Peggs said. “This is about collaborating to strengthen community through food, [which is] much more impactful for all concerned.”

In Boston, the 49-unit B. Good chain has tapped similar micro farmers.

Working with the hydroponic vertical farming company Freight Farms, which offers turnkey shipping container set ups dubbed Leafy Green Machines, the restaurant chain initially tried to set up a farmer next to one of the restaurants, but landlords wanted the farm to pay rent.

Instead, the grower found some unused space under a highway in downtown Boston where farmer Scott DeLuca set up his shipping container to supply B. Good locations nearby.

“It was good visibility and symbolic that you can grow produce anywhere,” said Jon Olinto, B.Good’s co-founder.

For about a year, the chain used DeLuca’s kale, which was more expensive than conventional, but the chain was happy to promote fresh kale smoothies in January when local greens weren’t available. Olinto said DeLuca was supplying about 75 to 100 pounds of kale per week.

Then B. Good, which has long tinkered with its own attempts at farming, decided to buy its own conventional farm on an island in the Boston harbor. The company decided to put all efforts toward that farm, though Olinto did not rule out the use of vertical farmers in future.

Distributors get into the game

In Detroit, wholesale distributor LaGrasso Brothers Produce in 2015 invested in a Leafy Green Machine set up in a warehouse to produce greens year round.

Tom LaGrasso, chief operations officer, said the company worked with local chefs to develop a proprietary mix of lettuces now available 52 weeks a year.

It’s sold at a premium, but it augments the limited growing season in Michigan, he said.

“We priced it so it met demand for the amount we were able to produce. But the response has been great,” he said. “Consumers really appreciate the story and the sustainability, along with the freshness and the fact that it’s supporting the local community.”

Some are hoping restaurants will soon be doing their own vertical farming.

Photo courtesy of Smallhold

On a much smaller scale, Smallhold in New York is selling subscription-supported mini-farms to grow mushrooms.

On a much smaller scale, Smallhold in New York is selling subscription-supported mini-farms to grow mushrooms.

The company has created mini shelf-sized units that can be installed on site at restaurants, said Adam DeMartino, co-founder.

Smallhold serves as the nursery to get the mushrooms started and then growing is completed at the restaurant. The cost ends up being about half the cost of distributor pricing, though he said it varies by type of mushroom.

The company also sells exotic mushrooms grown in a shipping container on the East River.

In Laramie, Wyo., Bright Agrotech produces vertical farming systems, such as ZipGrow walls used by restaurants like Altitude Chophouse & Brewery, also in Laramie.

Designed more typically to be used indoors, the restaurant decided to put the ZipGrow wall outdoors against a south-facing wall. During the spring and summer, the restaurant grows basil, cilantro, mint, oregano, dill, tomatoes, lettuces and kale, said owner Karen Robillard.

For about three years, the restaurant leased the equipment. But recently Robillard said they decided to buy it, which she said was roughly $2,000. The restaurant buys seedlings and pays a maintenance fee. A general manager does the daily pruning and picking and fills the system with water.

“It’s not physical, “she said. “It takes about an hour each morning. And mid season, the wall is a really beautiful showpiece.”

Robillard said the food costs savings will pay for the equipment in time.

“But it’s not something we did to save money,” she said. “It was really to provide our guests with something that’s picked same day and is really fresh. It’s the whole farm-to-table movement.”

Tommy Romano of Infinite Harvest (Photo by Danielle Lirette)

Tommy Romano of Infinite Harvest (Photo by Danielle Lirette)

Challenges to overcome

Vertical farmers Tommy Romano of Infinite Harvest, however, said he shies restaurant operators away from doing their own growing.

“It’s a good concept to get hyper local. But I ask them, ‘Are you a chef? Or are you a farmer? You can really only do one,’” he said.

Instead, Infinite Harvest offers chefs a subscription to a certain amount of growing space within his hydroponic vertical farm.

“They could pay month to month for X amount of square feet and grow whatever they want,” he said. The farm also supplies some 200 restaurants around Denver, both direct and through a local distributor, he said.

But like many disruptive new industries, urban farming already has casualties.

Farmed Here, an early pioneer operating a commercial hydroponic farm in Bedford Park, Ill., closed its doors for good in January, and plans for a second location in Kentucky were cancelled.

“It’s an emerging industry with a lot of players early on and there will be fall out,” said Romano.

Despite hyperbolic interest from investors and futurists, there are still hurdles to overcome, he said.

“There’s a resistance that some people have called overalls versus lab coats,” he said. “We’re the lab coats, but we’re trying to break down that barrier.”

A sampling of urban farming suppliers

AeroFarms: Newark, N.J.-based operator of indoor aeroponic facilities.

Bright Agrotech: Laramie, Wyo.-based maker of the vertical hydropnic or aquaponic ZipGrow Tower.

Edenworks: Brooklyn, N.Y.-based operator of vertical aquaponic farm that produces microgreens.

Freight Farms: Boston-based maker of the Leafy Green Machine shipping container units.

Go Green Agriculture: Encinitas, Calif.-based organic hydroponic indoor farm serving the Los Angeles area.

Gotham Greens: Operates more than 170,000 square feet of rooftop greenhouses across four facilities in New York and Chicago.

Grow Pod Solutions: Maker of “plug-and-grow” vertical farms in shipping containers using hydroponics.

Infinite Harvest: A 5,400-square-foot hydroponic vertical farm serving the Denver area.

Local Roots: Vernon, Calif.-based builder of indoor farms including the hydroponic TerraFarm.

Smallhold: New York-based maker of miniature vertical farms for restaurant kitchens.

Square Roots: New York-based accelerator that builds vertical farms in shipping containers.

Urban Seed: Operator of aeroponic greenhouses in Las Vegas that will produce 25 crops.